You’re a screenwriter. And you're SO stuck. Nothing is moving, nobody wants to make your movie. You are on a crusade for recognition, for people to tell you how great the idea and how successful you will be. But your phone calls are not being returned. Are you caught in the Draft One Trap?

You’re a screenwriter. And you're SO stuck. Nothing is moving, nobody wants to make your movie. You are on a crusade for recognition, for people to tell you how great the idea and how successful you will be. But your phone calls are not being returned. Are you caught in the Draft One Trap?

To appease your conscience you will make scene level tweaks. Lots of them. You will call it draft two, three, thirteen. The reality: this is still draft one. You will finally get sick of the script and move on to the next Great Idea. Years go by and many scripts may come from your hand but none will ever get made, let alone reach an audience.

Did you just recognise someone you know in the above description? Perhaps yourself? Do you really believe, off all the readers of all the blogs in all the world I'm trying to convert you? No. The above was taken from a promotional blurb I wrote for a two-day story workshop at Metroscreen.

The course will be partially about the foundations of screen story and partially about practical ways to apply them to your work. You may not need those foundations for draft one. The first draft is all about "Don't get it right, get it written." But then comes draft two and reality kicks in. If you haven't written your first draft yet, you still need to be aware of the elements that will come into play further down the road.

The course will be partially about the foundations of screen story and partially about practical ways to apply them to your work. You may not need those foundations for draft one. The first draft is all about "Don't get it right, get it written." But then comes draft two and reality kicks in. If you haven't written your first draft yet, you still need to be aware of the elements that will come into play further down the road.

Successful feature screenwriters don’t cherish that first draft. They know it is crap so they won’t show it to anyone let alone shop it around, except for advise on how to move to the next draft ASAP. Successful screenwriters listen to the honest constructive criticism from industry professionals and follow a process on the way to a wonderful, radically different Draft Two.

For these writers the second draft is an easier and more important leap forward than any next draft of the script. This has to do with the 'law of diminishing returns', but more about that in a later post on this blog.

Apart from making sure you will not unknowingly fall in that Draft One Trap ever again, the Metroscreen course will focus on most of those issues I have come across in unsuccessful scripts during my six years as a producer. The second day of the two-day course will show how to implement a writing process that may significantly speed up the development and create a genuine opportunity when pitching your projects to producers, directors or funding agencies.

If you are interested in this course or would like to know more, send me an email or contact Metroscreen. Or just download the enrolment form and send it in! If you're not a Metroscreen member, you can sort that out using this form.

But enough about me and my course.

TRIBE OR TRITE? STONEKING'S MANTRA

At a recent AWG NSW event poet and AFTRS teacher Billy Stoneking performed a short version of his 'tribe act'. Many in the audience were confused. And yes, over the years some have questioned the contribution of the national film school to Australian screenwriting culture. But rather than fueling the controversy, I would like to give Stoneking credit where credit is due.

Stoneking's 'tribe' theory focuses primarily on the writer's connection with both the material and the audience. If you think Stoneking has a purely artistic, individualistic approach to screenwriting, think again. He pays ample attention to the importance and the meaning of 'drama' and he acknowledges that a good movie is made for an audience. And not just 'an' audience: it must be

the audience you have - in some way or other - a connection with. Do read the article

here. Being a poet, the man masters his language in a way I can only envy.

If on the other hand you would like to

see the

entertainer Stoneking, you might be lucky enough to still find his

Sony Tropfest videocast of the 'tribe act'. Have fun!

HOLLYWOOD VS. OZZYWOOD

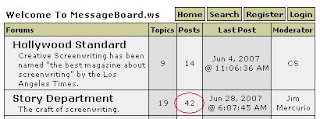

As you may have noticed from earlier posts on this blog, Creative Screenwriting Magazine is a personal favourite. It was recently named "the best magazine about screenwriting" by the Los Angeles Times.

As you may have noticed from earlier posts on this blog, Creative Screenwriting Magazine is a personal favourite. It was recently named "the best magazine about screenwriting" by the Los Angeles Times.

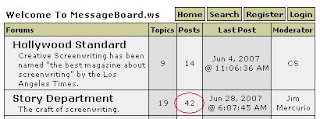

Their 'Story Department' (photo above) web forum opened in April 2006 and since then they have received 42 posts from writers all over the world.

Closer to home, four months ago some passionate story consultant opened a little forum on the bulletin board of the Australian Writers' Guild (photo left) to answer questions from writers.

The writers dropped by ... and they keep coming back! If you're an AWG member you should be able to check it out

here. If you're not, perhaps you should become an associate? The benefits are surely worth it.

WRITING FOR ACTORS

(Or: why writers should win the Best Acting awards)

Until recently I was only a producer and story consultant. I can now add 'writer' to my credits. Well, in spirit that is. The credit will never be on the screen. It was a rewrite-for-hire job and although in my humble opinion the story is now 200% better, the original writers will get the praise, if any. In any case, it is exciting to know after my rewrite the script was deemed ready for consideration by a Hollywood Studio (Fox) where it is at the time of writing.

But all that is beside the point. The project in question is supposed to launch the career of a particular actor, which I could hardly believe after reading the draft I received. The actor's character was NOT the story's protagonist, he had limited screentime and worst of all: he was given the most unspeakable dialogue.

Which set me thinking. How do you write dialogue for a beginning actor? You don't. You write

emotion. And emotion the actor will

not need to

perform. I have had this conversation a dozen times over the past month so I apologise in advance for those who have heard me preach about this before.

Let's go back about eighty years (or

ten blogs) to the work of

Lev Kuleshov (Photo: The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, 1924).

Kuleshov took unedited footage of a completely expressionless face [...] and intercut it with shots of three highly motivated objects: a bowl of hot soup, a dead woman lying in a coffin, and a little girl playing with a teddy bear.

Kuleshov took unedited footage of a completely expressionless face [...] and intercut it with shots of three highly motivated objects: a bowl of hot soup, a dead woman lying in a coffin, and a little girl playing with a teddy bear.

When the film strips were shown to randomly selected audiences, they invariably responded as though the actor's face had accurately portrayed the emotion appropriate to the intercut object.

As Pudovkin recalled: "The public raved about the acting of the artist. They pointed out the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, were touched and moved by the deep sorrow with which he looked on the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he surveyed the girl at play.

But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same." (from David Cook's splendid A HISTORY OF NARRATIVE FILM.)

These results are known today as the 'Kuleshov effect' and it explains why often actors win awards for performances they didn't give. When Russell Crowe broke onto the Hollywood scene with his nomination for

THE INSIDER, it had IMHO nothing to do with his acting skills but everything with Eric Roth and Michael Mann's terrific writing, which effectively projected the feelings we share with the Jeffrey Wigand character onto Crowe's blank face.

A more recent example is the late

Ulrich Mühe's performance in

THE LIVES OF OTHERS (Das Leben der Anderen), which won him numerous best actor awards including at the European Film Awards. The second half of the movie is an emotional powerhouse, yet the actor's face is near blank.

Conversely, great actors have been blamed of bad performances where the only culprit really was the screenwriter. The actor could have avoid the blame by politely passing on a screenplay that was not worthy of his attachment.

Bottom line: if you want to write great drama for any actor, irrespective of the experience level,

don't describe the emotion you want to see on the actor's face. Make the audience feel the emotion before the character has to respond to it. Great drama does not have visible emotion; it makes you, the audience

feel it. If you must, write a tear on an expressionless face.

Hitchcock would say: "I need actors who can do

nothing well." He understood perfectly that it was the writer's job to convey the emotion, not the actor's. He also perfectly understood the power of the

Kuleshov effect and consequently: the power of

editing.

Great actors are not those who can be express sadness, anger or desperation better than others. Great actors are those who can pick great scripts.

AUSTRALIAN FILM: FRANK COX AND ERIC BANA

Frank Cox of

Hopscotch can help greenlight a feature film. He is one of the 'good guys': he looks at films that don't necessarily fill the multiplexes. Better even: he reads those screenplays. But that doesn't mean he will be betting the house.

"I ask 'Who do you think the film is for?' Some of them say 'Frank, I make movies for myself, because I'm an artist and the audiences will follow it if I do something fantastic. I've got a vision." "And I'm going 'Good on you, if you've got the stuff to do this and you find a market, fantastic. But if you're not going to talk to me while you've got these ideas, then don’t come to me at the end and get disappointed if I tell you I don’t know what to do with it.'"I had to think of these words tonight while I was watching a freshly shot Australian film (I'm bound by secrecy as it's not out yet). Multi-protagonist, not done badly but just not good enough. Another case of

"I've got a vision"... In today's market, anybody with a brain would steer away from multi-protagonist for a first feature. But what I found completely baffling was the fact that a government agency had put money in the project, both for development AND production. What are we doing? Anyhow, where does Frank Cox see the current Australian cinema?

"Australian films are a bit of a question mark." The talent is certainly there, proved by the success of Australian industry people overseas, but "It seems to me that most projects in Australia are hurried. In other words, the development process lacks, the stories are not fully developed, and they don't reach their optimum because everyone seems to be in a hurry to put their film in development and then production." It's a familiar story; the problem is understood throughout the industry."Thank you to ScreenHub for the kind permission to re-publish. You can read the full interview here.

here.

Recently a good friend and fellow Belgian interviewed Eric Bana in Rome for his latest

LUCKY YOU (another

Eric Roth screenplay). My friend asked his opinion about Australian film and I have a funny feeling he would not have given this answer to a reporter on Australian soil:

"It may sound weird but working in Australia is not that important to me. It can even be dangerous to a career."

[...]

"I know an 'international name' can help, for instance if you want to get a high budget film financed or if you want to launch a difficult project. But as I said, there is a real danger. You receive a lot of scripts that aren't ready. The producers then believe a big name will solve the problem. So I am very careful"THE STORY DEPT.: FROM IDEA TO PRINT

My preparations for the Metroscreen course explain why it's been a bit quiet in The Story Dept.; for the other reason behind the temporary silence I have to profoundly thank many of you, the readers of this blog! Over the past months I have been increasingly busy as a story consultant, both on projects in development as some films in post-production.

My preparations for the Metroscreen course explain why it's been a bit quiet in The Story Dept.; for the other reason behind the temporary silence I have to profoundly thank many of you, the readers of this blog! Over the past months I have been increasingly busy as a story consultant, both on projects in development as some films in post-production.

Indeed the principles of story don't stop with the shooting script. From a story perspective the assembled footage is a work that hardly ever reflects the story beats exactly as they were intended in the script. Or if they are, sometimes a better option becomes apparent in the editing suite.

For a team that has laboured over the same movie for months or years, it is hard to make far-reaching decisions without being consumed by feelings of insecurity and doubt. Fortunately there may be a guiding light as the principles of story still apply! If areas of the story don't work for the outsider, sometimes the reasons can be found in a breach of (one or some of) those principles. Enter the story analyst!

Next to the consultancy work I have been happily producing the short animation ACID SUN (photo) by writer/director/animator Rodney March. The third OZZYWOOD short film is also the first one rigorously co-developed in terms of story and I am hopeful this will bear fruit at the film festivals once it will hit the screens later this year.

Next to the consultancy work I have been happily producing the short animation ACID SUN (photo) by writer/director/animator Rodney March. The third OZZYWOOD short film is also the first one rigorously co-developed in terms of story and I am hopeful this will bear fruit at the film festivals once it will hit the screens later this year.

As a matter of fact the validity of my mission as a story consultant (see 'about us') has been proven repeatedly over the past year. It's been a wonderful ride and I hope my clients agree even if it has been rough at times. I have seen filmmakers look at their works with professional and passionate scrutiny, think outside the box and at the same time question the reasons and motivations behind their stories. In most if not all of the cases we have improved their works, sometimes immensely, resulting in a marketable draft, a re-energised development process or at worst: an improved insight in the mechanics of story structure and the dynamics of our film industry.

THE QUIZ

If you have taken the quiz before and failed miserably, try again. Most likely it was not because you can't see the difference between a main plot and a subplot but ... you only had 3.7 secs to type in your answer. That has been fixed, so you can now improve your score!

If you have taken the quiz before and failed miserably, try again. Most likely it was not because you can't see the difference between a main plot and a subplot but ... you only had 3.7 secs to type in your answer. That has been fixed, so you can now improve your score!

To pass you need to answer 14 out of 20 questions correctly. The quiz is definitely not for beginners but most of the answers can be found somewhere in the articles of this blog. Click through to see your score and the right answers. Finally you'll be guided back to the OZZYWOOD web site. Good luck!

http://ozzywood.com/quiz

Congrats to Nathan Fielding, recipient of the Monte Miller Award '07! Nathan walked away from the awards last night in Sydney with a broad smile and a cheque of $5,000.

Congrats to Nathan Fielding, recipient of the Monte Miller Award '07! Nathan walked away from the awards last night in Sydney with a broad smile and a cheque of $5,000.